Difference between revisions of "Tagger Microscope Box Design"

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The project that I am working on with Dr. Jones and his UConn lab group is the mechanical design of the tagger microscope box. The tagger microscope is a critical part of the GlueX particle accelerator experiment being constructed and run at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Virginia. The GlueX project is overseen (and largely-funded) by the United States Department of Energy, but is executed by an international collaboration of physicists which includes students and faculty members from universities in the US, Canada, Chile, the United Kingdom, Greece, Armenia, and China. | The project that I am working on with Dr. Jones and his UConn lab group is the mechanical design of the tagger microscope box. The tagger microscope is a critical part of the GlueX particle accelerator experiment being constructed and run at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Virginia. The GlueX project is overseen (and largely-funded) by the United States Department of Energy, but is executed by an international collaboration of physicists which includes students and faculty members from universities in the US, Canada, Chile, the United Kingdom, Greece, Armenia, and China. | ||

| − | + | The GlueX experiment is designed to probe the mechanisms of confinement of quarks and gluons inside hadrons. Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the accepted theory of the nuclear strong force which explains the interactions of the quarks and gluons that compose hadrons. Quarks and gluons are subatomic particles which never live in isolation, but are always bound inside composite objects called hadrons. Gluons are the force that holds quarks together inside hadrons is the gluon field. Different hadrons are distinguished by a unique set of quantum numbers for J (spin), P (parity), and C (charge conjugation) and flavor. Hadrons come in two types: mesons existing in their simple state of bound quark/antiquark, and baryons in simplest form of three quarks. Mesons consist of only two fermions, and provides a unique opportunity for studying strong-interacting physics. Such an opportunity is analagous to the hydrogen atom in classical physics. | |

| − | + | The idea of confinement was proposed as a way to explain how quarks and gluons are the elementary particles of which the nucleus is made, even though isolated quarks and gluons have never been observed in an experiment. The proposal of quark confinement states that an infinite amount of energy is required to isolate a quark outside of a hadron. One of the predictions of QCD is that the gluonic field inside hadrons will have an independent degree of freedom from the quarks, and will be capable of being independently excited. The energies and mode structures of the excitations can give important information regarding the configuration of the gluonic fields, which ultimately give rise to confinement. The GlueX experiment searches for mesons with internal gluon excitations, called "exotic mesons". GlueX will map exotic mesons by protucing them with photon-proton collisions and subsequently measuring their quantum numbers by studying the angular distributions of their decay particles. Ultimately, if GlueX is successful it will be the first time that such exotic mesons have been observed experimentally. | |

| + | |||

| + | The GlueX experiment will generate a photon beam beginning with a 12gev electron beam from the CEBAF accelerator at Jefferson National Laboratories. GlueX will subsequently use the coherent bremsstrahlung technique to linearly-polarize this photon beam. The photon beam will then pass through a solenoid-based hermetic detector which is being designed to collect data on meson production and decay. Using the tagged bremsstrahlung technique, electromagnetic radiation is produced by the deceleration of electrons inside a component called the radiator. After they emerge from the radiator, a magnetic spectrometer called the "tagger" will measure the remaining energy of the electrons. The energy in the photon beam is thus "tagged" by the energy of the beam minus the energy of the electrons measured in the tagger. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This project concerns the design andconstruction of the electron detectors that measure the energy and timing of the electrons in the tagger. A prototype for the tagging detectors - colloqually known as the "microscope" - is currently being designed and constructed at UConn. The entire prototype will be complete in December 2009 and will be tested during early 2010 in an electron beam at Jefferson National Laboratory in Virginia. | ||

During the fall 2008 semester, a huge development in the project is the finalization of a design for the “skeleton” framework that will both support and contain the electronic, optical, and mechanical components of the microscope. To do this, TurboCad drafting software was used to create ANSI-standardized renderings of the different pieces that will ultimately come together to form the skeleton. The idea for a skeleton framework for the actual microscope box was decided on as a way to conserve weight in the final design. The final design must also be light-sealed and durable, and the contents of the box must be easily accessible for routine maintenance. All of these specific considerations were taken into account when designing the tagger microscope's skeleton (and complete box), and all of the details of this work are described below. | During the fall 2008 semester, a huge development in the project is the finalization of a design for the “skeleton” framework that will both support and contain the electronic, optical, and mechanical components of the microscope. To do this, TurboCad drafting software was used to create ANSI-standardized renderings of the different pieces that will ultimately come together to form the skeleton. The idea for a skeleton framework for the actual microscope box was decided on as a way to conserve weight in the final design. The final design must also be light-sealed and durable, and the contents of the box must be easily accessible for routine maintenance. All of these specific considerations were taken into account when designing the tagger microscope's skeleton (and complete box), and all of the details of this work are described below. | ||

Revision as of 22:00, 10 February 2009

About Me

I am a 6th semester Physics major in UConn's Honors program, and I have been working with Dr. Jones and his lab group since more-or-less the beginning of summer 2008. This is the first Wiki page I have ever made, so please excuse any errors (although any feedback would be great). I intend to update this regularly as my work on the mechanical design of the tagger microscope progresses. Currently I am almost finished with the TurboCad renderings for the skeleton of the prototype tagger box. I hope to have it assembled by early 2009.

Project Overview

The project that I am working on with Dr. Jones and his UConn lab group is the mechanical design of the tagger microscope box. The tagger microscope is a critical part of the GlueX particle accelerator experiment being constructed and run at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Virginia. The GlueX project is overseen (and largely-funded) by the United States Department of Energy, but is executed by an international collaboration of physicists which includes students and faculty members from universities in the US, Canada, Chile, the United Kingdom, Greece, Armenia, and China.

The GlueX experiment is designed to probe the mechanisms of confinement of quarks and gluons inside hadrons. Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the accepted theory of the nuclear strong force which explains the interactions of the quarks and gluons that compose hadrons. Quarks and gluons are subatomic particles which never live in isolation, but are always bound inside composite objects called hadrons. Gluons are the force that holds quarks together inside hadrons is the gluon field. Different hadrons are distinguished by a unique set of quantum numbers for J (spin), P (parity), and C (charge conjugation) and flavor. Hadrons come in two types: mesons existing in their simple state of bound quark/antiquark, and baryons in simplest form of three quarks. Mesons consist of only two fermions, and provides a unique opportunity for studying strong-interacting physics. Such an opportunity is analagous to the hydrogen atom in classical physics.

The idea of confinement was proposed as a way to explain how quarks and gluons are the elementary particles of which the nucleus is made, even though isolated quarks and gluons have never been observed in an experiment. The proposal of quark confinement states that an infinite amount of energy is required to isolate a quark outside of a hadron. One of the predictions of QCD is that the gluonic field inside hadrons will have an independent degree of freedom from the quarks, and will be capable of being independently excited. The energies and mode structures of the excitations can give important information regarding the configuration of the gluonic fields, which ultimately give rise to confinement. The GlueX experiment searches for mesons with internal gluon excitations, called "exotic mesons". GlueX will map exotic mesons by protucing them with photon-proton collisions and subsequently measuring their quantum numbers by studying the angular distributions of their decay particles. Ultimately, if GlueX is successful it will be the first time that such exotic mesons have been observed experimentally.

The GlueX experiment will generate a photon beam beginning with a 12gev electron beam from the CEBAF accelerator at Jefferson National Laboratories. GlueX will subsequently use the coherent bremsstrahlung technique to linearly-polarize this photon beam. The photon beam will then pass through a solenoid-based hermetic detector which is being designed to collect data on meson production and decay. Using the tagged bremsstrahlung technique, electromagnetic radiation is produced by the deceleration of electrons inside a component called the radiator. After they emerge from the radiator, a magnetic spectrometer called the "tagger" will measure the remaining energy of the electrons. The energy in the photon beam is thus "tagged" by the energy of the beam minus the energy of the electrons measured in the tagger.

This project concerns the design andconstruction of the electron detectors that measure the energy and timing of the electrons in the tagger. A prototype for the tagging detectors - colloqually known as the "microscope" - is currently being designed and constructed at UConn. The entire prototype will be complete in December 2009 and will be tested during early 2010 in an electron beam at Jefferson National Laboratory in Virginia.

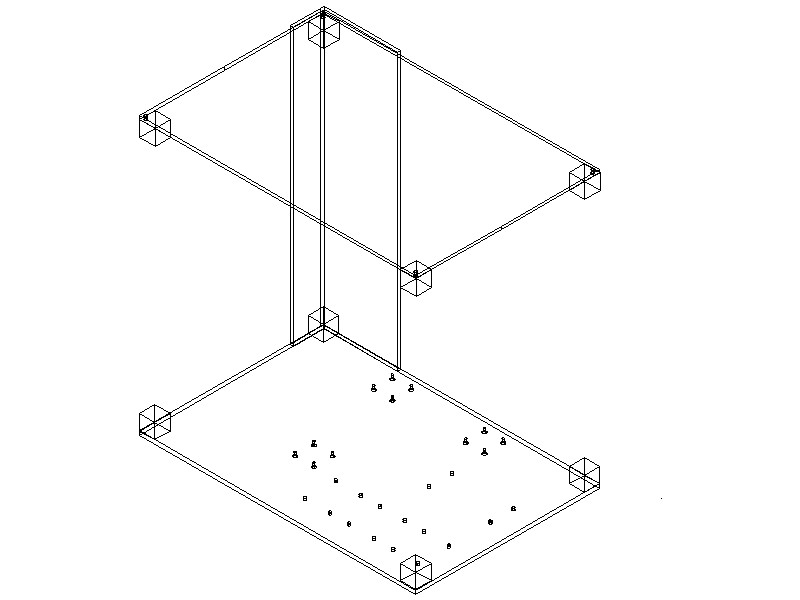

During the fall 2008 semester, a huge development in the project is the finalization of a design for the “skeleton” framework that will both support and contain the electronic, optical, and mechanical components of the microscope. To do this, TurboCad drafting software was used to create ANSI-standardized renderings of the different pieces that will ultimately come together to form the skeleton. The idea for a skeleton framework for the actual microscope box was decided on as a way to conserve weight in the final design. The final design must also be light-sealed and durable, and the contents of the box must be easily accessible for routine maintenance. All of these specific considerations were taken into account when designing the tagger microscope's skeleton (and complete box), and all of the details of this work are described below.

Summary of Work during the Fall 2008 Semester

This semester, my work focused on the physics-engineering design of the tagger microscope box to be used for the GlueX particle accelerator project in Hall D at Jefferson National Lab in Virginia. The volume of work that I ultimately produced was not as much as I had hoped for, because I spent the first months of the semester learning the computer programs needed to facilitate my design work. Based on my current knowledge of these programs plus the final data and design files I was able to create, I would consider this semester a definite success.

The main computer program used for my project is TurboCad. TurboCad is a drafting program similar to both AutoCAD and Solid Works, but is better suited to my project because it allows more 2D and isometric views, as well as a full repertoire of snaps and rendering settings. The currently-marketed edition of TurboCad is Version 15.0, but for the GlueX design project I was working primarily with Version 12.0. It took some time into the semester until I could properly install it on my personal laptop, but after that time my work became infinitely more efficient. The TurboCad program was somewhat complicated to learn, but I did so successfully by using the help menus and tutorials, as well as by asking questions at lab meetings and experimenting on my own. The first challenge I gave myself was drafting a a bicycle frame (exactly proportioned to my size), and once I succeeded at this near the end of October, I began working exclusively on the Tagger design. The files I created for the Tagger design still need a lot of revision, which I hope to complete over the winter break and into next semester. Ideally, I would like to have the prototype Tagger box machined and assembled by sometime in February of 2009.

This semester, I learned that the process of designing the Tagger box is entirely experimental. Overall as a lab group, we have a general idea of how the box should be constructed, although this is subject to slight revisions on a weekly basis. Some of the main revisions integrated into the design this semester include the “skeleton” support structure versus a solid box to reduce weight, and the idea of using foil to form the sides of the box to access the fibers and motors inside. As each of these revisions was discussed and sketched out, it was my job to draft the new design in TurboCad – a process that became a great learning experience for me on many levels. In this same vein, I would characterize the entire Fall 2008 semester as a “great learning experience” for my design project. The presentable TurboCad files that I have created are indexed below. While they are not many in number, I believe that they accurately represent my growing confidence and comfort level with using the program. The majority of the Tagger’s skeleton is rendered, and I hope to work with our lab group and the Physics machine shop to expand on all of these designs in the coming weeks and months. For this semester, however, I feel that my greatest victory was learning the TurboCad program, which will be an invaluable tool for me to use in the future.

Fall 2008 Annotated Index of TurboCad Files

- Bicycle Frame

This is the initial challenge I gave myself in TurboCad. Now it doesn’t seem like a challenge to draft this, which shows the progress I made this semester. I don’t know why I included this; I just thought it was fun. - Tagger Base Plate

This is the base plate for the Tagger box, with holes indicated for the motors, power supplies, and screws. I initially drafted this in the wrong format on TurboCad, so Igor had to help with the revisions. - Tagger Top Plate

This is the top plate for the Tagger box. No significant holes are indicated yet, but Woody’s backplane design is still being finalized. Once the backplane is finished I will integrate space for it into the top plate rendering. - Tagger Custom Skeleton Corner

This is the one corner piece of the Tagger skeleton that will be machined at UConn, because one side is slightly longer to allow for holes to be cut so that important cables can pass through. The other three corners will be cut from angled aluminum stock which will be purchased by our lab / the machine shop. - Tagger Skeleton Assembly/Exploded View

This is a view of all of the previously described parts as they come together to form the Tagger skeleton. Only parts that will be manufactured in the Physics department machine shop are shown.

Spring 2009 Updates

I am very excited that as of 27 January we have finally ordered the aluminum metal for the tagger box! Working with the lab group and the UConn Physics machine shop, I hope to have the prototype box assembled by early February. I will hopefully post pictures as soon as construction begins.

As of 5 February, I am working closely with the UConn Physics machine shop to both create the tagger box and learn the CNC machining tools necessary to complete such construction work with minimal assistance in the future. The machine shop is busy with another project right now, but we will begin making the box late this week (week of 2/9-2/13) and early next week.